Show Summary

Live from Roots on the Narrow Gauge, Tom Russell shares about his early musical influences, personal encounters with the Beatles and Bob Dylan, living in Nigeria, the making of The Man from God Knows Where and Hotwalker, bad gigs, and his writing process. He tops it off with a new song.

Intro

Train sounds recorded by Andy Hedges on the Cumbres & Toltec Narrow Gauge Railroad in Chama, New Mexico

Andy reads the poem “From a Railway Carriage” by Robert Louis Stevenson, from A Child's Garden of Verses (1885).

Quotes from this Episode

“I’m always thinking of songs, 24/7.” – Tom Russell

Links for this Episode

Find out more about Tom Russell.

Find out more about Roots on the Rails.

Tom Russell albums:

Pictured above: Andy Hedges, Nadine & Tom Russell, and Ramblin' Jack Elliott at the Rainbow Man Gallery in Santa Fe during the Roots on the Narrow Gauge train trip.

Credits

Recorded, edited, and produced by Andy Hedges.

Theme music: Texas Traveler by Hal Cannon.

This episode was recorded in front of a live audience at the Grand Imperial Hotel in Silverton, Colorado during the Roots on the Narrow Gauge train trip.

Contact

andy@andyhedges.com

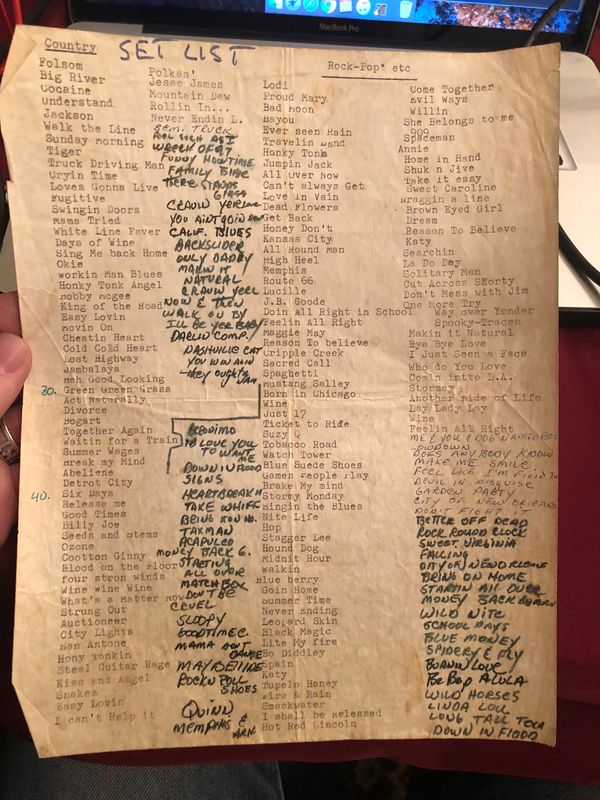

Pictured above: Tom Russell's setlist from Skidrow, Vancouver.

Transcript

Tom Russell Interview

(Railroad sounds)

Andy: That’s the sound of an old narrow gauge railroad in Chama, New Mexico. Last month I had the privilege of being a part of the Roots on the Narrow Gauge, a train and road trip across New Mexico and Colorado with Tom Russell and Ramblin’ Jack Elliott. I drove Ramblin’ Jack from town to town and the three of us played shows every night and I recorded the interview you’re going to listen to today. A big thank you to Tom Russell and the Roots on the Rails folks for inviting me to be a part of the Roots on the Narrow Gauge. I really can’t say enough good things about that trip and if you are interested in going on a trip like that in the future, check out Roots on the Rails at www.rootsontherails.com . I’d like to start today’s show with a poem written by Robert Louis Stevenson in 1885. This piece is entitled, “From a Railway Carriage”.

(Andy recites “From a Railway Carriage”)

(Theme music enters)

Andy: Howdy folks, this is Andy Hedges and you’re listening to Cowboy Crossroads. On each episode, I interview a different guest and ask them to share stories and discuss music, poetry, and culture from the working cowboy West and beyond. My guest today is songwriter Tom Russell. I interviewed Tom on the show last year, and if you haven’t listened to that yet, you might want to go back. I recorded today’s interview in front of a live audience inside of the Grand Imperial Hotel in Silverton, Colorado, during the Roots on the Narrow Gauge train trip. Here’s Tom Russell.

(Theme music fades)

Tom: I grew up, you know, born in the late ’40’s and the ’50’s of LA, I’m writing a few songs about it now and working on a novel, as I’ve said for the last fifty years. I had one novel, crime novel, published in Norway that I think it was Carol or someone said they had it. I think it’s in Norwegian, thank God, and I’m working on another just for fun. That’s my third occupation! (laughs) So LA in the fifties and what’s fascinating about it - well many things. My father was an Iowa farm boy, a horseman, that came West, talking a lot about that on a record called The Man From God Knows Where. He came from horse traders that came from Ireland, he had one Norwegian background, got all that on the record. And he headed out West and went for the American Dream, you know, and he ended up in jail for three months. He went to far, some kind of blue collar crime. I was a teenager, very significant. But horses were always there. As I wrote in the book, Ceremonies of the Horseman, my brother’s obsessed with it - Jack knows my brother. My brother’s three or four years older, he’s probably one of the top horsemen in California. He’s a livestock contractor, which means he’s the guy behind the scenes at the rodeos and the high end cutting horse things, if you don’t know what it is. I never got into it, but a lot of people with money, there’s some cattle in the arena, maybe what twenty head of cattle. A guy goes in with a high end quarter horse and the horse does all the work and gets one cow out and keeps it out, and you know it’s not all that exciting to me, but they need a lot of cows so my brother is dealing with a thousand head of cattle every week, where he gets them and this and that. He has a ranch in northern California. Anyway, my brother’s playing cowboy records in the early fifties, he’s got a huge stack of Hank Williams 78’s and Tex Ritter 78’s, first Johnny Cash record, which is called the Hot and Blue Guitars of Johnny Cash, it’s got a deco cover on it, not even Johnny Cash’s picture. He gave it to me, I’ve still got it, it’s got a deco cover of these guitars, and he’s playing all this stuff non stop and he’s the horseman. The minute he sees the horse, I’ve rarely seen him off a horse. My father meanwhile is investing all our money in racing horses, claiming horses, you buy a horse cheap at the track and you try to move em up, you know. So he’s up and down. My brother hangs out at the track, Hollywood Park, which no longer exists. My brother hot walks horses which once the horse comes off the track you have to walk a thoroughbred to cool them down, they’re such hot blooded animals, dangerous animals. But, he got on a horse and never looked back. So we had horses as kid, and he built a bucking barrel in the backyard out of a forty gallon oil drum suspended on garage door springs and that’s how he practiced his bull riding, proceeded to launch the neighborhood kids into outer space and then they decided they didn’t want to be bull riders. You had to do what Pat told you. You have to do, like Casey would or something, “Ride a bull”, you had to say it, all the words right, you know, and he’d launch me, and I knew right away I wasn’t gonna be a rodeo guy. But he played all this music and one summer he ran off into the mountains, the Sierra Nevadas mineral king Yosemite and packed mules for tourists, like Ross Knox did in the Grand Canyon, packed tourists back in for two weeks and every guy that packed had to know twenty cowboy songs at night and recitations, very much like you do - Face on the Bar Room Floor and those old Tex Ritter songs. So he came back with a ton of cowboy songs and meanwhile back at the ranch, back at the house, suburban house in Englewood, my mom’s playing more sophisticated music, Broadway musicals, which I’m also into, that’s where the Rose of Roscrae came from. So we were hearing Oklahoma and Annie Get Your Gun and stuff like that, and going to see the musicals, the Music Man, and this all rubbed off on me. And then her brother, whose passed, whose name is George Malloy, was a classical pianist and a good friend of mine. He never married, he ended up in New York in a rent controlled apartment on 72nd and Broadway, near where John Lennon got shot and I was in town that day, playing behind opera singers and touring the world and at the march on Washington, Martin Luther King march on Washington, Roberta Peters was supposed to sing the national anthem before Dylan and Joan Baez sang. Dylan sang When the Ships Come In and Only Upon In Your Game - that’s on YouTube - and the Star Spangled Banner is on YouTube. You can barely see my uncle, but somebody didn’t show and they called my uncle out of the audience and he played behind this African American singer named Camilla Williams, the Star Spangled Banner. And I learned all this stuff when he was kinda on his death bed. I mean, we knew he was a big time guy. But the other thing was, he played in a couple movies because he was in the union. So, he’d get a call, a western movie downtown. You’re playing, like this guy playing in the saloon in our hotel, bar room cowboy piano. So he’d get a part in a lot of these movies as a pianist. So all this stuff was kinda going around, and then I, kinda the introverted kid believe it or not, got into folk music big time. I was an athlete first, a football player and my room was covered in colored pictures of athletes, boxers, and rodeo guys. And then I got into the Kingston Trio and the Limelighters, the commercial end. And then I discovered Ramblin’ Jack and the blues guys. I got to see Mississippi John Hurt and Mance Lipscomb and Dave Van Ronk and then I got to see Ian and Sylvia at the Ashgrove

Andy: What point in all this did you pick up a guitar yourself?

Tom: Well my brother, God bless him, has kind of atonal voice. He would love to be a singer but he can’t sing in tune and he’s been chewing tobacco since he was twenty. If you met him here, you wouldn’t believe he was my brother because he’s like Slim Pickens. He worked with Casey Tibbs, he worked with a lot of people. And he knows that L.A. horse scene in the fifties and he keeps pushing me to do something about it because he says, “There’s a hundred thousand horses here and no one really remembers all that. Stables and western movies.” But anyway, he had a guitar. He bought it in Tijuana, a gut string guitar and he just wasn’t gettin’ anywhere on it and I stole it from him. Somebody said “You’ve got to stop that godawful noise that’s coming out of your brother’s bedroom.” And so I kinda learned some chords and messed around, but I didn’t have any - you know, I was kinda scared of singing in front of people for a long time. I didn’t develop much stage presence till down the line, you know. I had to pay my dues after college. So I got my first guitar, my first good guitar, before I went to Africa in 1967, back when you could walk, like Guy said, into a pawn shop and there’d be a couple of old Martins. You can’t do that now in a pawn shop. You know it was the 1946 D-18 beat to hell. Whoever was playing this guitar played it, and it’s just like it was except for the bullet hole that’s in the back. Now, we can get to that, but it was a hundred and fifty bucks and its still got the same tuning pegs and everything. And I started to get a little better on that and I took it to Africa with me in 1969 for a year and I started playing and I hung out with so many academic people, I decided I didn’t want to hang out with any more academic people. I was gonna to start at the bottom in the music business and so I ended up on Skid Row in Vancouver.

Andy: Before we get to that, how did the move to Africa happen? And the Criminology degree - where in the world did all that come from?

Tom: I was a genius at one time. (laughs) No, what happened was, if I put it together quickly, well, there were a lot of cool stories. Anyway, I had this career as a kid because I was obsessed with music as the world’s greatest gig crasher. So if I wanted to go see Ramblin’ Jack or Mississippi John or Dylan or the Beatles, I didn’t have enough money, I snuck in somewhere. And I had all these - I don’t know where this came from - but I’d go to the back of the theatre and when the first show let out, I’d walk in backwards talking about I’d lost my wallet or something. I had this stuff that worked. So, I’m going to get to how I got to college, but with the Beatles - I was a big guy, played defensive right end on a really good team, but, 210 pounds or something - the Beatles, I jumped in front of their car in front of the Hollywood Bowl and started telling people to get out of the way and went right in past security. And this is in the newspaper, I got it, in the L.A. Herald. And they thought I was a security guard opening the door let John and Paul get out and John said, “I couldn’t have done it without ya.” And they went on stage. So I was, I don’t know, I was kinda this part time criminal and I met Bob Dylan because I got into his dressing room. (Knocks) “Uh, I got a telegram for Bob Dylan!” And I had a telegram for Bob Dylan, cause I took it from the messenger, who didn’t know who Bob Dylan was. “I work with Bobby, I’ll take it in there.” And he goes, “Are you sure?” He goes, “Nobody but me and gives Bobby this telegram.” I guess it, obviously you can tell from my personality, which I have about ten of ‘em, I could pull it off and I was big enough. And Dylan looked at me and, “Yeah, thanks man.” And after the show, he looked at me cause I stayed near our stage and he laughed when he passed me on the stage. You know, he liked that kind of thing and he rolled down the window in the parking lot, he was with Bobby Neuworth, who I know now and he said, “Hey, telegram boy. Come over here.” I go “Oh shit!” And my friends are going, “Shit man! You shoulda never done that!” He goes, “Let me ask you a question.” And, you know, by this time I’m idolizing the guy, and he goes, “Tell me something. Tell me right now. Where’s the nearest liquor store?” And I go, “I don’t know. I’m fifteen.” You know, and the guy behind me is eighteen driving the guy and he goes, “I know where it is Bobby. Follow us.” So I go, “Shit! What do you do?”, you know, and we get in the car, Dylan follows us, four guys in his car, down Santa Monica Boulevard. It was the Santa Monica civic. First light. Second light. There’s right behind us, you know. I’m going, “You idiot!” He goes, “Man, we’re just going to keep going down the road, we’re travelin’ with Bob Dylan!” I go, “You better find a liquor store!” You know, we’re lookin’ for signs. Fourth light, Dylan’s had enough. He’s in the driver’s seat, he’s already got a bottle of Beaujolais. So he jumps out of the car, and I’ve this affirmed, and dances around our car laughing at us. And we thought, “He’s got a gun” or something. And he was just messing with us. Really cool, you know, like in, got back in the car, they drove around us into history. And I wondered if I dreamt that, and a guy that’s coming to my show next week in LA, he goes, “Everything you said is true. He did that.” You know, so that was the one time I met Dylan. But anyway, then I’ll get you to Nigeria quickly now, because that’s how I got into college. My grades weren’t great, I mean, I went to a Catholic boys school, Loyola High, cause I could play football. And, yeah, it was a good school. Lots of literature. Ten of these guys are coming to my show in LA next Sunday. But, we were the number two team in the nation in 1964 and I have a song about it on Folk Hotel. I met Jack Kennedy at the LA Coliseum. Once again, I was the kid who walked up to his car back when you’d want to do it and stuck my hand and said, you know, I said, “Good luck.” And I had to play a football game in there on the night when he was shot. So I have a song about that called Rise Up Handsome Johnny. So, I didn’t have good enough grades to get into the University of California Santa Barbara. I don’t know why, I think I’m doing a police report here. (Laughs) But I think it’s kinda funny, but I told them I had a letter from Mayor Sam Yorty of LA. And so I wrote Sam Yorty and said, “You know, I helped you on your campaign. Can you write me a letter of recommendation?” And he did. And it got me into the university, which I was not really qualified to take these classes and I flunked out in six months. Went to junior college for a year. Got interested in sociology, got a little more mature and came back to the University of California. Met a guy - and this will get us to Africa - named Bill Chambliss, high, very high end criminologist, and, he’s passed away five or six years ago. Cool dude, he played Leonard Cohen songs. We drank wine together, we played Leonard Cohen songs, we bought horses together. He was my kind of guy, you know. He had a wife and three kids. So he gets a gig from the Rockefeller Foundation in Africa in Nigeria for a year. So he wants to take some African American guys over. Well, meanwhile, the riots are started all over and they’re burning the university down and they’re burning the Bank of America down and none of these guys could go so he finally asked me, “You wanna go as my student teacher to Nigeria?” Well I didn’t really know where Nigeria was at the time. I go, “Ok.” And he said ok, blah, blah, blah, we’ll get you the money and it came through, and the gig came through. And what I didn’t know, what I wasn’t aware of at the time was they were just finishing up the Biafran War, which was a hairy, one of the worst wars of all time. I don’t know how many millions of people were killed. It was a tribal war between the Yoruba, the dominant tribe, and the Igbos, which are down in eastern Nigeria, and it had a lot to do with oil. There’s a lot of oil down there. We were two hundred miles from the front line but still there was a lot of gun - I got arrested coming off the plane for taking pictures in a war zone and I had no clue. And a Rockefeller guy grabbed the guy right away and bribed him, and so they let me in the country. I got arrested going out of the country a year later for something, and I learned how to bribe. Always people were pointing guns in your face, you know, so we kinda hid near the university. I started playing more guitar and teaching a little, but it was in the middle of a war so you kinda tried to stay away from trouble. But, I’d go down to some of these bars I’d get to play with King Sunni Ade who had a steel guitar player, “Get that white kid up here!” I’d play one chord, they’d play a song that last for an hour and a half. You wouldn’t hear this on a record. And one day they kinda end up with the talking drum thing. The university had twenty talking drummers at an exhibition playing this beautiful drum music and standing in back was a white woman - look like Betty Davis - elderly white woman. At the time I thought that she was around sixty. I asked somebody, “Who’s that? She’s telling the drummers what to do?” They said, “That's Susanne Wenger. Don’t go over to her. She won’t talk to you in English. She speaks Yoruba.” Well it turned out she went over there with a white anthropologist and ran off with a primitive Nigerian drummer and went into the forrest and became a white priestess up in Oshogbo which is in my song “East of Woodstock” and developed this art community up country. So I got up and went up and tried to talk to her once, but she didn’t speak English. But you can see her on YouTube. She passed away. She was 100, heavy duty person. All this stuff was going down to the marketplace and got a guy to teach me how to carve wood cause I knew I wasn’t going to go any further in the academic trade so I played. Came back a year later and with a lot of African art and ended up in Vancouver on Skid Row with my band, the Mule Train Review - Skid Row’s finest band.

(Theme Music enters)

Andy: Tom Russell has three concept records that he’s referred to as his “American Trilogy”. This includes the albums The Man From God Knows Where, Hotwalker, and The Rose of Roscrae. These recordings are unlike anything else you’ve ever heard and are favorites among Tom Russell fans. I asked Tom to talk about where those concepts came from.

(Theme Music fades)

Tom: Well two things, going back to when I talked about what I listened to as a kid - folk music, cowboy music, but Broadway musicals. I was obsessed, kind of, with the Broadway musicals of the ’40’s and ’50’s. Those were the good years, you know. And Rogers & Hammerstein, and - who is the other guy - Lerner and Loewe. I just read Lerner’s books, I should’ve known that. They did GiGi and they did My Fair Lady, which we just saw on Broadway. What I always liked were the minor characters. They’d steal the shows. And when Les Mis, Master of the House - it’s the minor characters. The writing in those musicals, it’s just tremendous. Recently I met a great great musical singer from Germany named Florian Schneider who sings, who is a big star in Germany and Switzerland. He and I are going to do a record. We’re going to go back and forth with some Irish songs. A tremendous singer, but anyway, I was kinda obsessed with the form of taking a group of 10 or 15 songs and making a musical out of it. Man From God Knows Where, thank God it was funded by a Christian, Norwegian Christian label in Norway, which had a lot of money. Told them I wanted to do a song cycle about my ancestors, most of whom came from Ireland. But one main guy came from Bergen, Norway; and I’ve always connected with Norway and done pretty well there. Used to play there two months at a time with Andy and the band and Fats. But, so, this was 15 years ago - I don’t know when that record came out. But he said “Let’s do it if you’ve got the songs.” And I said, “I must’ve because it comes right out of my ancestors mouth.” I had the journals and everything. “We came here and it was rough. And we cleared forty acres of land. And the people from the Civil War came back. And we made whiskey.” I had all of the information, ending up with my old man in jail and the horse stuff there. Throwing horse shoes at the moon. So he says, “Let’s do it.” So he rents a farmhouse, a historic farmhouse on the West coast of Norway near the Hardangerfjord and he hires the best folk musicians in Norway and the best singers and brings some people over from Ireland, including Dolores Keane, one of the greatest singers that ever came out of Ireland. She’s still alive and quite a drinker. And I’ve got a lot of good stories about her. She traveled with Nancy Griffith. But, Dave Van Ronk is the only one, he did his part in New York because he couldn’t come over. And Iris Dement came over. And we lived in this farmhouse for two weeks and it had a setup in the ballroom like this, and we would have a catered dinner and breakfast every day. And then we’d go in with these great musicians. I’d show em the song and then he put the record together. And it went out and I guess it was on HighTone. It was on the Norwegian record label and then HighTone.. It actually did very well. It was reviewed in the New York Times and Atlantic Monthly. So I had the urge to do that, not ever thinking. I thought it might end up as a musical, which I guess it’s been in a few productions in colleges. And Hotwalker came from, I was working on another record - I think Borderland - and somehow I heard the voice of Little Jack Horton. “Don’t you start on me! Some people creep me out.” And he just kept talking to me, and talking to me. I thought, “Man, I want to do a spoken word record and get some of my heroes in there.” I knew Charles Bukowsky and met him once - that’s a whole other funny story - on Hollywood & Vine. Corresponded for forty years, thirty years, and there’s a book of our correspondence out. But, he’s on the record, a funny vignette. Kerouac is on the record. God, a dozen American voices that spoke to me and we got the ok to use them as songs. We didn’t go beyond two minutes or something. And Edward Abbey’s on the record. And I wove music and Little Jack’s voice in there as the narrator. There’s two main songs on there. There’s Grapevine, that’s about when you come over the grapevine hill from LA down into the great San Joaquin Valley. There’s Bakersfield over here. I didn’t mention that music. That’s another music I grew up on. Buck Owens, Merle Haggard, Wynn Stewart. That’s going to be the sound of my next record that I’m cutting in a few weeks in Austin with Bill Kerchen. Nadine loves Bakersfield music and she loves Bill Kerchen, so we’re going to get that sound. I’m writing some country songs. So Grapevine is on that record and a song about Woody Guthrie I think. Called up Ramblin’ Jack in the middle of the night and I said, “I’m going to record this, Jack. Tell me about Woody.” And you can hear him on there go, “Well Woody, he was a strange guy. Nobody really liked him much, except for his songs.” And then I go into this song Woodrow. And see, that’s stuff that I like that, because not a lot of people - Pete Seeger wouldn’t say that. And Woody was a strange guy. Like, his wife said he’d go out for a cigarette and he’d be gone for two months, you know. He’d run off with a woman or something. Woody had some wild side. Same way with Phil Ochs. Everybody worships Phil Ochs, except when he was down and out, as Dave Van Ronk, who you dig I know, and Dave was a good friend of mine, said, “They didn’t really want to know Phil when he was lyin’ in the gutter. They stepped over him.” To me, that’s heartbreaking. So I tried to get out somewhere.

(Theme music enters)

Andy: On my last interview with Tom, he shared some stories of bad gigs and later mentioned to me that there were plenty more for another episode.

(Theme music fades)

Tom: I mean, just last month, a month ago. A couple of things. Every night on Skid Row could have been a bad gig. You’d look out, a cop came in one night said, “There are eight felonies a night committed in this club. We’re going to close it down.” Because you could see people being rolled and thrown out in the alley. The alley was horrible, you know. Skid death row. Meth and all that stuff. And then Onyx and Pharaoh and Onyx’s lover got shot one night in a club. But just last month, two months ago, cause it can happen anytime, but I had this concept, we’re over in Switzerland all summer. We played Holland, Norway, Finland, Germany. But then I was kinda idle, and I was writing songs, painting, but I wanted to play. I figured I’d create this alter ego called “Country" Johnny from Ft. Worth, USA, playing “Country” music. And I was going to go down to these country bars near us in Bern that featured these guys that don’t really make it in the States. So they go over to Europe, and just because they say they’re from Fort Worth. And then they play background music like we did in country bars and get paid fifty bucks a night. And I go, “I’ll do that just for kicks! Cause I can sing all these songs.” And my wife - and everybody’s- kinda, “I don’t know.” And we go back to one of the gigs I used to play when I had a band. And he says, “Tom, I don’t know. People are gonna know who you are. I don’t think you can pull this off.” And I go, “Yeah, but it’d be funny.” And he goes, “I don’t know Tom.” So a guy across the street from our apartment has his sixtieth birthday and we meet him in New York. He’s coming back to Switzerland and he says, “Why don’t you sing some songs?” And he’s about fifty employees, young guys, woodworkers, having a hundred people there, a catered BBQ and he says, “You can be the entertainment!” And I go, “Yeah, Country Johnny!” (laughs). So we give ‘em a wrap. He doesn’t speak English that good. “Don’t tell these people who Tom is really, cause, you know, Tom has records out. He was on Letterman. I don’t want people coming around the apartment. But you can tell ‘em, when you introduce ‘em, you can say ‘He has records.’” So he does the opposite. They build a big stage. They get a PA system. There’s a hundred people there, drinking beer; and the guys, the young guys, who I know are gonna be trouble are down there on the other end of the room cause it’s World Cup time. I think it’s near the end of World Cup time. All they wanna do is drink the free beer and watch the soccer game. I don’t blame them. Then here’s all these tables that he expects are gonna fill up with people that are gonna go nuts, you know. He gets up there and she would have to translate what he’s saying, but he basically said, “Well, there’s some American guy, lives next door, that wants to sing some songs.” People are going, “What?” He goes, “Hey, my next door neighbor wants to sing. Can he get up and sing?” So they went further into the corner and were talking, all these guys, and watching soccer. Nadine and her mom are sitting in front of me, along with the guy. I didn’t realize till later what he said, but I’d of course be over in the corner too drinking beer. I slowly won about ten people over, you know, and some gals started dancing, and some of the guys saying, “Hey, he’s pretty good!” But after 35, 40 minutes of doing Folsom Prison Blues and every trick in the book, I was pretty much done. I got off stage. Her mom asked me, “So Country Johnny, when’s the next gig?” (Laughs) That’s it! So you learn a bad gig can happen - it doesn’t happen that much any more - but I’ve learned to deal with it. I worked in a comedy bar once in San Francisco in the late ’70’s when I got out of music for a little while. Robin Williams would come in to work on his chops. He was in Mork & Mindy, he was starting to be really famous. He’d come in and get behind the bar with me and pour beer and do routines. I saw him take somebody apart one night on stage, just a little fifty seat club. A woman started heckling him. I watched him artistically take her apart in about twenty minutes so when she left the club she looked like fifty years older than when she walked in. I was absorbing all this. Like whoa man. I don’t get heckled much any more. We had a sold out show in Santa Fe a few years ago and one of my fans - a lady fan - I didn’t know she was a fan. Why someone would pay thirty or forty dollars to come in and heckle you? She was about ten feet away, drunk, and give me a bad time. You know, the thing about handling a heckler is, in the end you know you’re alone mostly. A security guy isn’t going to come down, and you’re making the rest of the audience uncomfortable if you get angry. You can’t get angry. You’ve got to do it in a humorous way. So I had repartee with her and eventually calmed her down, you know, but people were getting nervous. And then it got funny, and when it gets funny the tension goes away. A bad gig can happen eventually.

Andy: How’d you get the hole in that guitar?

Tom: Well, during that time I was driving cab in New York when the first group broke up - Hardin and Russell - Patricia Hardin was a classical pianist from Texas and I moved from Vancouver to Austin because I heard about the Austin scene. I took a Greyhound Ameripass bus pass across the US and sang on the Grand Ole Opry with Kinky Friedman. I told that story to somebody. Stopped in Austin in 1972 and all these people were coming there like Willie was showing up and Townes and Guy. I knew these guys were the real thing, you know. Big time songwriters. Jerry Jeff. I was just starting to write songs and I thought moving to Austin.. and met Patricia Hardin, she was in a band and we formed a duo and we were getting pretty good. We had a record offer from Vanguard Records that had Joan Baez, had turned down Bob Dylan before he went to Columbia. We thought we’d hit the big time right off the bat and we got, I don’t know what we did, but we got too pushy with them and wanted to hire a producer they didn’t want to hire, and they didn’t do the deal. So we made two records on our own. Only record I’ve had reviewed in the Rolling Stone was the first record called Ring of Bone. This was interesting. She was a very good musician and a very good singer and we won the Kerrville New Folk in ’73 or ’74. Anyway, broke up in San Francisco. Worked in a comedy bar. Moved to New York to try to start over and started driving cab. Later I picked up Robert Hunger, but I got kinda down and out cause I was driving six at night until six at morning which made you kinda nuts cause you couldn’t find your sleep cycle anymore. So I was gettin’ kinda out there and a guy came to New York that I knew from San Francisco, whose father owned a carnival, a traveling carnival. He was from Montreal and he was going to set up the biggest carnival in world in Puerto Rico - San Juan, Puerto Rico. This was ’81,’82, the time of the great urban cowboy scare. You had mechanical bucking bulls in bars and you had to play Cotton Eyed Joe on the fiddle cause that movie with John Travolta was a big deal that started the two step and the line dancing phase in the ’80’s and the bucking bulls. So they had a bucking bull down at this carnival and a huge tent and they needed a country singer. So he said, “You wanna go down there? We’ll pay you five hundred bucks a week for two months.” And we got a band and everybody around in New York was saying, “Go, go! Get back into the business, man. You’re going nuts.” So I flew down there and most of it’s in the song called The Road to (?). And the band turned out to be a ten piece disco band from Montreal and they weren’t really into Tom Russell’s Johnny Cash imitations. (Laughs). I had written Gallo De Cielo by then, which I sang for Robert Hunter - that got me back into the business. I was singing Gallo every night. The band, they were called Fussy Cussy. They were from Montreal. Famous. They weren’t into the band, the stuff I was doing. Drinking, a lot of drinking was going on. The Puerto Ricans weren’t much into either. They were into salsa and “When’s the music start?” So it was a lot of aggravation. A lot of the carnies liked me. I learned a lot about the carnival business. There was a big woman named Gypsy, weighed about four hundred pounds, took care of me kinda. Like, “Don’t give Tom any shit. I like what he’s doin’.” But the security guards didn’t like me, so I made the mistake one night of leaving my D18 in the dressing room and some guy used it for target practice, his buddy told me. They put it up on the wall and shot it with, put a 22 pistol in the sound hole and shot the back out. Said, “Tell ‘em next time, he’ll be playin’ it.” Yikes. So the vibe started going bad and then the tropical storm started. And a lot of the carnies - and there were hundreds of them - they’re different people with a different language like little Jack. They started getting violent and some guy got up on a high wire - there was a high wire going across the whole carnival, and some drunk got up there one night and fell off. Things like that started happening. They had a freak show, two headed cow or something, and somebody stole it. The vibes were rotten and I knew the owner of the carnival and he says, “Time for you to get out of here, it’s gonna get bad.” His wife went around somewhere and got me a big shopping bag full of fives and ones and twenties and said, “Catch the next flight out.” And there’s about a thousand bucks in there. And I went home finally, a month in to the carnie with my shot up guitar.

(Theme music enters)

(Theme music fades)

Andy: I’d like to talk about your writing a bit. I’m curious about what your writing process looks like these days - if you write on the road or at home or certain times of the day or if you have a routine or just wait for the inspiration to strike.

Tom: Both, both. Yeah, I mean both. A little of both. But, I do work every day. As I say, we live part time in Switzerland in a farm town where there’s a lot of horses and cows and I like the atmostpheere. There’s pretty of road houses down the road with plenty of good food. But it’s inspirational. And then we’ve been living in Santa Fe, which is inspirational too. We built me a big studio and I’m looking out at the desert and I have my painting studio and that’s going really well cause my biggest gallery - which we are going to go thru at the end of this sojourn - is in downtown Santa Fe called the Rainbow Man. Interesting gallery, because beyond the Tom Russell room is the Edward Curtis photographs. This guy’s an authority on him and Edward Curtis did all the famous photos of Native Americans back at the turn of the century; and he’s also an authority on Pendleton trade blankets. And he’ll be there. Bob Capone, give you a little talk. Interesting guy. And I’ll show you my stuff. So I get up in the morning and do a little yoga. Nadine’s a yoga instructor and she knows a lot about exercise and food and that helps on the road. And we walk, you know, usually walk an hour a day, and then it’s time to go to work. Usually a paint a little to loosen up and then I have to play guitar every day. So I pick up - it’s a physical - it’s something I told Tyson last week, “Are you playing guitar?” You know, cause Jack is amazing, I think he’s still playing damn good. But you have to play every day because of your hands and your callouses and your wrists. So I play, try to play 30, 40 minutes a day. It can be boring because there’s no feedback. You’re playing to the wall, but generally that starts a song or I’ll have a big stack of papers here. I’ve got about 12 songs for the next record and I’m working on them constantly to try to tighten them up. I just demoed them in Santa Fe and now I want to listen to them on the road and see if they hold up before I play them for a band. So I’m probably working on songs… There’s a lot of time in Switzerland because there’s nothing else, no TV. Nadine goes out, does a lot of yoga. They have a routine. So I work two or three hours every day at writing and I’m working on a western novel for fun again. I’m always working on an essay. Somebody like Range Magazine or Folk magazine will ask me to write about something and I’ll be happy to because I like the process. I have that book of essays “Ceremonies of the Horseman” when I was writing five thousand word pieces for Bill Reynolds and that was a great magazine, it was just, he put too much money into it. It was so good. So I’m working on essays and the novel a little bit and the songs. The songs are number one, always number one. And then paintings probably number two because it’s so peaceful. And she’s got me standing up all day. I never sit down anymore. So the computer, if I’m writing on the computer, it’s stacked up here, you know, on books. Cause, like, Hemmingway, when I got into his house in Cuba, Hemmingway always wrote standing up. You know, there’s something about it, but it works. You don’t get tired as much and man, you get a break. So, I’m going around in a circle, kind of, I’m painting a small room in Switzerland, a big room in Santa Fe. Working on this painting of Ramblin’ Jack, working on a song, then an essay. That goes on four or five hours a day until happy hour. Man, God created happy hour. And then, you know, cause for a good reason - I don’t drink that much - but, the same way after the show, I like to have a good drink because there’s a time when you want to unplug. Because I’m always thinking of songs. 24/7. And, you know, I can’t do that all night long. The process is something like that.

Andy: When we were emailing you said to ask you about a couple of cowboy tunes you’re working on.

Tom: The record starts off with a song about Kerouac that’s got a country beat, and a good friend, whose become a good friend, I’ve never met him, is Douglas Brinkley, who lives in Austin, he’s a CNN commentator. Douglas knows Ramblin’ Jack and Douglas edited Jack Kerouac journals, which are quite fascinating. You don’t get a real idea of Kerouac until you read his journals, about how hard he worked. Sleeping with his mother out on Ocean Parkway in Brooklyn and writing sundown to sunup before he even published a novel. But anyways, a song about Kerouac and a song called Small Engine Repair, that I talked about, about a guy that fixed my lawnmower. There’s a song called Isodore Gonzalez. He’s mentioned in my essay on Buffalo Bill in Europe. And Isodore Gonzales was a real person. He was a Mexican guy who dressed up, you know, in a sombrero, and the big thing, and rode a bronc thru the arena. Two shows a day, and a horse rode over on him and he got killed. He’s buried in Bristol, England. He was from Monterrey, Mexico. So I wrote a corrido about him that will have accordion. It's a cowboy song. And then - this is good - there’s a song called Pass Me the Gun Billy. I don’t know if we talked about this, but I’m living with my brother Pat when I flunked out of college for the first time. Went up to play football at a junior college in San Luis Obispo called Cuesta and that’s when I quit my football career. I wasn’t into playing in 110 heat, you know. I wanted to play guitar. Anyway, I’m living with my brother out on at the end of Edna Road in San Luis Obispo and my brother’s always up for trouble of any kind - cowboy trouble. And we’re watching TV and he says, “Turn the TV down. I just heard a gun shot.” I go, “What?” I go, “Oh God.” He goes, “Somebody’s poaching cattle out in the pasture. Call Billy.” Billy Milla, who still works with him. “Call Billy down the road and tell him to cut the road off.” He looks out and he sees a car out there. Some kind of Hudson, some creepy old car. Somebody has shot something on his property. You don’t do that to a cowboy rancher. And he goes, “Get your stuff, we’re going after him.” Jump in the truck with my brother and he takes off and down, out the front gate. He’s got a dog in the back, Australian Shepherd. Down the road to Billy Milla’s house. Well, Billy’s out there waiting and Billy jumps in and he goes, “Where are they? They didn't come by here." They went the side road to the Pacific Ocean to a place called Okie Flats, Oso Flaco. “Let's go, get in Billy!” He takes off, 90 miles an hour down that side road, and I'm in the middle going, "Holy shit, let me out of here!" Cause he gets right up on the guys. I could tell right away this is gonna go bad cause this guy turns around and looks. There’s two of ‘em, and right away I know it’s going to be Deliverance and we’re going to be bent over the log (laughs), cause that's what these guys looks like. And my brother’s playing the big tough cowboy, “C’mon Billy.” Boom. We hit the Pacific Coast. We go over 101. They go under 101 and they pull off into the ditch and wildflower bed. I'm rhyming all this into the song I'm working on. There's four of 'em in the car and tree of them get out with shotguns and aim it right at the truck and our truck comes to a halt about five, ten yards away. One of those things when a phrase comes into your life that you never forget, when my brother turns over, pushes me out of the way, and goes, “Pass me the gun Billy!” And Billy goes, "Pat, we ain't got no gun!" And I go, "Holy shit!” And I put my head under the dashboard and my brother’s put in the car and he goes, "Billy, where the hell's the gun?” And he goes, “Pat, we ain't never got a gun!” (Laughs) And they're about ready to, and they don't shoot. And the end of the story - and this is all gonna be in the song - (sings) “Pass me the gun Billy. We ain’t got no gun" - my brother's gonna love this. And Billy, who shows up at the gigs, every time I mention that story, everybody goes, “Did that happen?" It's like the same way people ask me about the Bob Dylan. Well, yeah, that happened. So we pull off, get away, call the cops. The cops come, they take us to the guy's house, and they've got 'em in handcuffs. It turns out they've got to be identified. Old man is up at the house, got a bonfire ready, guy is from Arkansas. They just robbed two liquor stores. You could tell these people were bad, bad trouble, you know. Last thing the cop says to my brother, "Next time you boys go to chasing poachers, you might wanna pack your gun." So that's all in the song. So those are two cowboy kind of songs. You had to have been there to have felt the tension.

(Theme music enters)

(Theme music fades)

Tom: So I was just working, and this was just kinda funny, so I’ll do it and it’s kinda cowboy. It’s my GPS love song. You know how addicted we have to be to GPSs and it makes me nervous cause I was, you know, from the old day of atlases. I like to see the distance between El Paso and New York, which is approximately 3,600 miles. 1,800 miles of it is Texas. I like to see it. Well, those days are gone, you know. I looked out on our balcony in Switzerland and every day this same old hawk comes over and says hello. And every time I’m out on the interstate I see a hawk out there and these are the guys that really have a GPS; so here’s my GPS love song. I hope nobody steals it. I’ll try to remember it. It’s called The Back Streets of Love.

(Plays The Back Streets of Love)

(Audience claps)

(Theme music enters)

Andy: Alright folks, that’s it for today’s episode. I’d like to thank Tom Russell for taking the time to visit with me. You can find out more about Tom at www.tomrussell.com . I’d like to thank the folks with Roots on the Rails for arranging for me to do this live interview with Tom. You can find out more about Roots on the Rails at www.rootsontherails.com . You can find out more about me and this show at www.andyhedges.com . If you’re enjoying this show and would like to help me keep it going, you can make a donation on the website; or, you can take the time to leave a review and a five star rating on the iTunes store; and you can take the time to tell a friend to give this show a listen. If you’d like to contact me with a question or a comment, or a story, I’d love to hear from you. Send an email to andy@andyhedges.com . Thank you for listening to Cowboy Crossroads.

(Theme music fades)